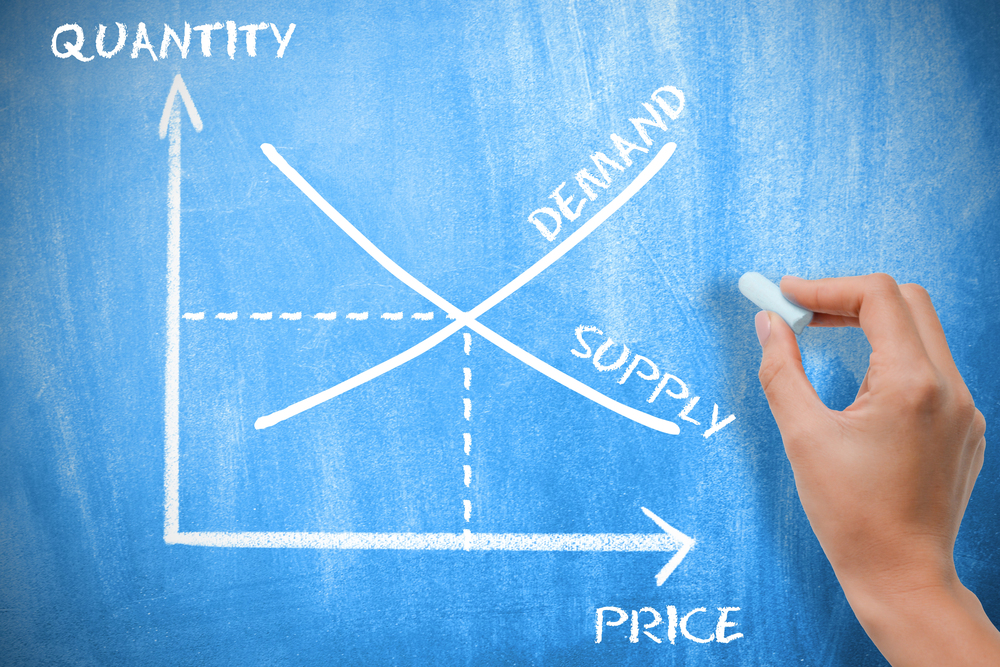

Each semester that I teach Principles of Microeconomics, I have some variation of this question on my exams:

- “Joe works at the local supermarket. One day, he says to you: ‘On Monday, we were selling oranges for $0.75 each and we sold 200 that day. On Friday, oranges were $1.00 and we sold 400 that day. The price went up, and so did the quantity demanded! The law of demand must be wrong!’ Evaluate Joe’s statement using the economic way of thinking. Is he right or wrong? Why?”

(If you would like to answer for yourself, Dear Reader, stop reading here and pick up with the next paragraph once you are done)

The answer I am looking for is something along these lines:

- “Joe’s statement is incorrect. The law of demand is a ceteris paribus statement. All else held equal, as prices rise, quantity demanded will fall. But what Joe witnesses can easily be explained by an increase in demand. That will cause both the price to rise and the quantity demanded to rise as the increase in demand means buyers are willing to pay more for the same quantity.”

The pedagogical lesson I want students to take away from this question is that whenever someone claims to overturn a scientific law, we should be skeptical. Existing theory can often explain the observed phenomenon. In this case, the law of demand is indeed a scientific law, the validity of which has been tested time and time again. And the incentives to find exceptions are quite strong. To quote George Stigler from his classic The Theory of Price:

In other words, to say that the law of demand doesn’t hold is an extraordinarily strong claim.

Of course, every once in a while, someone builds a theoretical model of a violation of the law of demand. Sometimes, they even include an investigation of one such good that seems to break the law of demand. But, upon further investigation, such examples break down, and the law of demand holds true. Strong evidence is needed for strong claims.

I think of this exam question whenever I read some economic commentator claiming that international trade has weakened America. Such an outcome would be unprecedented. Millennia of experience and evidence suggest trade strengthens nations and that turning away from it weakens them. This is explained by (and is evidence for) the law of comparative advantage. As with the law of demand, anyone who can provide robust and rigorous evidence overturning our understanding of trade will be guaranteed all sorts of professional and pecuniary honors. Despite these incentives, no evidence is forthcoming. Most of the claims that these well-established economic rules have been overturned are made in op-eds and are decidedly lacking in scientific merit.1

None of this is to say that a scientific law can never be overturned. Scientific knowledge is an ever-evolving thing. Miasma theory was backed by millennia of experience and evidence. Yet, it was eventually exposed as incorrect. And that is evidence of my argument. Those who overturned miasma theory are immortal names in the scientific world: John Snow, Louis Pasteur, and Robert Koch.

Could our understanding of international trade and the law of demand suffer the same fate as miasma theory? Of course. But those attempts to overturn the scientific laws need extraordinary evidentiary backing. Thus far, the evidentiary backing for overturning economic laws has been lackluster at best, and often outright false.

Footnotes

[1] Note: the claim “trade weakens a nation” is different from the claim “protectionism grows a nation.” The latter still argues that trade improves a nation, just that protectionism creates more prosperity.

(0 COMMENTS)