The surge of attention around the claim that a U.S. family of four now requires roughly $140,000 to live sustainably should be understood not as a debate over a specific figure, but as evidence of a structural disconnect between official economic metrics and the lived experience of households. At YourDailyAnalysis, we view this discussion as a symptom of a broader crisis in how economic well-being is measured.

The federal poverty threshold, designed in the 1960s, reflected the cost structure of an industrial-era economy in which food represented the primary constraint on household budgets. Today’s economy has shifted the burden toward services and mandatory expenditures that behave very differently: they rise faster than incomes, offer limited scope for individual optimization, and cannot be scaled down without eroding social and economic stability. From the perspective of YourDailyAnalysis, this shift renders legacy thresholds analytically obsolete, even if they remain in formal use.

The central contribution of the $140,000 argument lies not in the number itself, but in its articulation of the pressures facing middle-income households. What is often described as an “income valley” reflects a structural feature of the modern system: as earnings rise, households lose eligibility for benefits, face higher tax burdens, and incur additional costs tied to dual-income employment. The result is that marginal income gains frequently translate into far less financial resilience than expected.

At YourDailyAnalysis, we see this dynamic as the core reason why households with ostensibly high incomes often report persistent financial stress. The issue is not poverty in the traditional sense, but a lack of flexibility – limited capacity to save, adjust employment paths, absorb shocks, or plan long term without heightened risk.

Methodological critiques of the underlying calculations, including regional variation and category-level assumptions, are valid but do not undermine the broader conclusion. Even under more conservative scenarios, the income level required for a stable standard of living in many U.S. regions sits well above what is conventionally associated with middle-class comfort. In our assessment, the precise number matters less than the magnitude of the gap between statistical benchmarks and household reality.

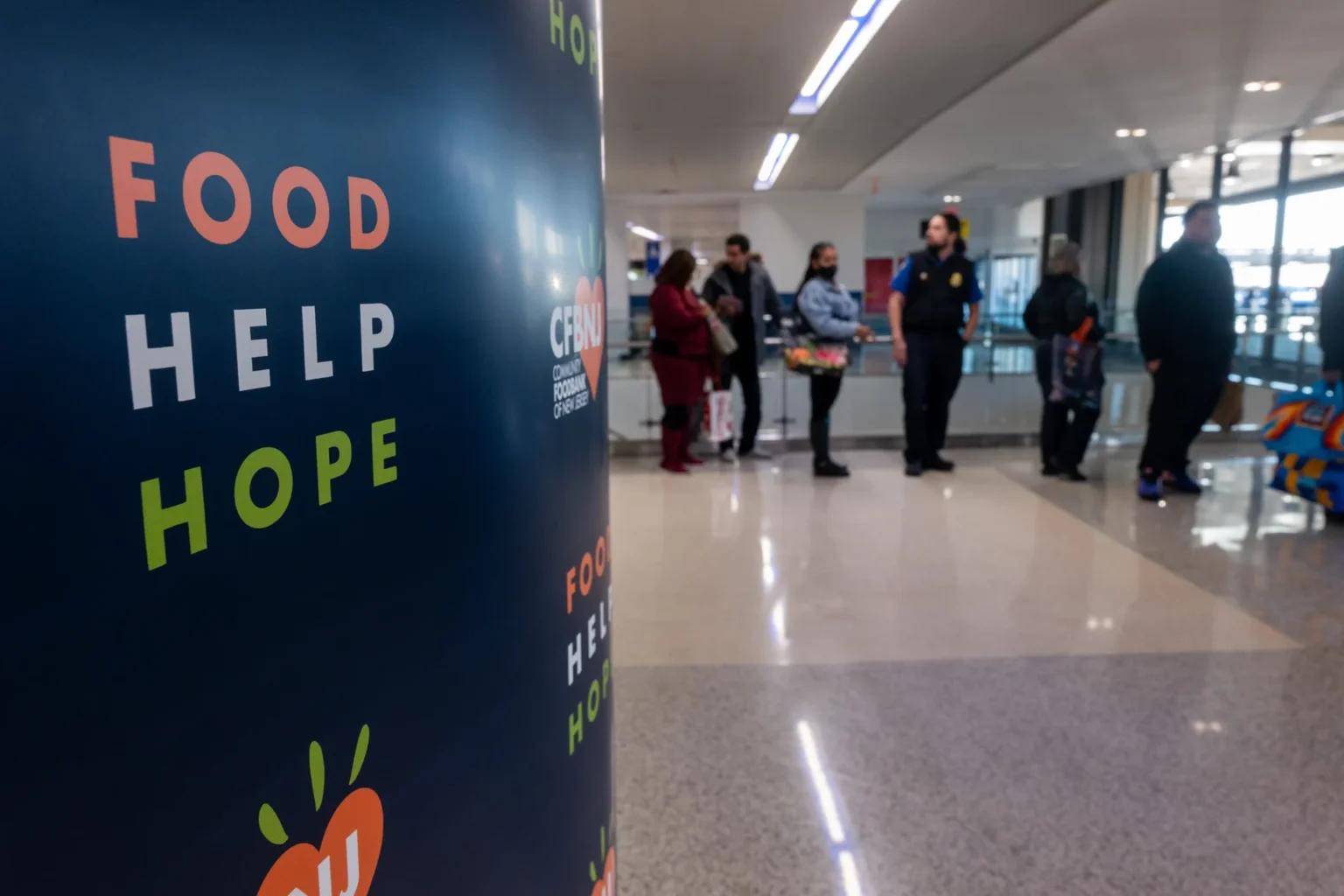

The debate over so-called “non-essential” expenses further illustrates this disconnect. Attempts to exclude digital connectivity, internet access, or educational support from baseline needs reflect outdated assumptions about participation in modern economic life. These costs now serve an infrastructural function, enabling access to work, schooling, and essential services. Ignoring them distorts the true cost of economic inclusion.

The viral spread of this argument signals eroding trust in traditional indicators of prosperity. When headline data suggest stability while large segments of the population experience ongoing financial pressure, the resulting gap carries economic as well as political implications. At Your Daily Analysis, we interpret this as a risk of rising frustration among households that fall outside formal assistance frameworks yet remain structurally vulnerable.

Our core conclusion at YourDailyAnalysis is that $140,000 is not a new poverty line in a technical sense, but rather a proxy for the cost of maintaining economic stability under today’s expenditure structure. It reflects the price of participation, not mere subsistence.

Looking ahead, we expect growing pressure to reassess how well-being is defined and measured, with policy debates shifting away from income thresholds toward the composition and rigidity of household expenses. For economic policymakers, this implies a need to focus less on transfers and more on reducing structural cost drivers – particularly in housing, healthcare, childcare, and education.

From a household perspective, the critical variable is no longer nominal income, but the durability of the overall financial structure. Until this reality is reflected in official metrics and policy design, the gap between economic statistics and perceived well-being is likely to persist across economic cycles.